Knowledge Hub

Ending malnutrition by 2030 – the battle is not yet won

After decades of decline, world hunger levels are increasing, and now stand at 821 million in 2017, one in every nine people, according to the recently released The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018.

For 50 years Concern has been at the forefront of tackling hunger and malnutrition in some of the world’s poorest countries. That there appears to be a reversal in progress is deeply, deeply worrying to us. It signifies that much more must be done if we are to achieve zero hunger by 2030 as set out in the Sustainable Development Goals. Yet this does not deter our will to keep working towards it.

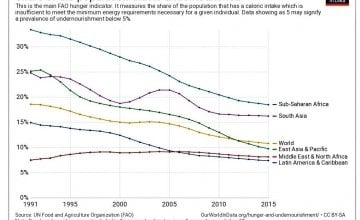

We have come a long way in reducing global hunger since the 1990s in nearly all regions of the world, and this achievement, and seeing all there is yet to achieve, motivates us towards our ultimate goal of ending hunger and malnutrition in the next decade. We cannot let things slide further backwards. Our work has become more important than ever before.

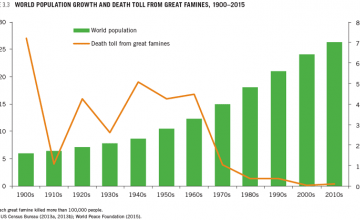

In the early- and mid- 20th century the downward trend in famines and associated mortality was largely led by changes in the geo-political landscape, increased global prosperity, food production, and globalisation, and growing responsiveness of the international community. However after years of decline, 2016 saw the risk of four concurrent famines - in South Sudan, Somalia, Yemen, and parts of Nigeria.

The commonalities across these complex food crises are striking - exacerbation by conflict, extreme weather related events, fragile institutional structures, and weak international policies and proactivity. Indeed, hunger and malnourishment in fragile states only seems to show signs of worsening, with 60% of the world’s hungry now living in such countries. It is a self-defeating circle – conflict increases food insecurity and food and nutrition insecurity increase the likelihood of unrest, violence and conflict. It is not surprising that countries such as Central African Republic, South Sudan, Chad, Niger, and Burundi that have some of the highest rates of childhood stunting and wasting are also at the bottom of the Human Development Index. Moreover, by 2030, more than half of the world’s poor are expected to live in fragile contexts.

Addressing hunger and malnutrition in these countries is by no means simple. What is needed is a conflict-sensitive approach that aligns humanitarian assistance, long-term development, conflict mitigation and peace building.

What needs to be done

There is no denying that short-term humanitarian assistance for the poorest and most vulnerable, displaced populations, children and women has been an urgent need. However, long-term development efforts to improve nutrition and food security, livelihoods and health, which are also inter-linked, are imperative to shift the needle towards greater resilience and reduced vulnerability. As the FAO report shows, access to safe, nutritious, and sufficient food needs to be framed as a human right, with priority being given to the most vulnerable groups. When poor people have enough nutritious food they are more likely to lead healthier and productive lives, less likely to be burdened by healthcare costs, and also less likely to take drastic decisions that impoverish them in the longer term.

We also need to find ways to address the root causes of conflict and inequality, especially as 10 of the 13 major food crises in 2016 were conflict driven. Our efforts on malnutrition and resilience cannot bear fruit until we invest in peace building– particularly given the number of countries that have been marred by prolonged conflict.

In addition, in 2017, 14 of the 34 countries in ‘food-crisis’ experienced the concomitant impact of conflict and climate shocks, such as prolonged droughts.

If we are serious about tackling hunger, then the international community must take a multi-pronged and better-aligned approach to sustainably improve food security and nutrition. Commitments such as the Grand Bargain for humanitarian action, and the recent UN conflict and hunger resolution 2417 serve as an important guidance for donors (both bilateral and multilateral), the UN, civil society, and governments to work in greater harmony.

As Concern marks 50 years, our commitment to tackling hunger and malnutrition, humanitarian assistance, and resilience efforts stands as strong as it did in response to the famine in Biafra, Nigeria. We know that in working with others who share the same vision, we will be able to build a better future for the millions who are currently entrenched in the hunger, malnutrition, vulnerability and poverty cycle. Ten years is not long, but it is long enough to bring transformational change.

Anushree Rao

Senior Policy Officer (Nutrition)