Knowledge Hub

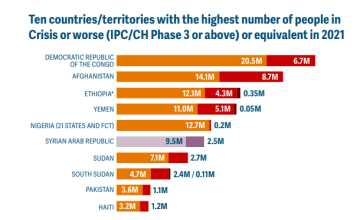

In 2021,193 million people in 53 countries faced acute food insecurity, meaning they were unable to consume enough adequate food, putting their lives or livelihoods in immediate danger. This is an increase of 40 million compared to 2020.

These stark findings are from the most recent Global Report on Food Crises* (4th May 2022) which also highlighted that a further 236 million people are under stressed conditions, on the brink of acute hunger. If acute food insecurity isn’t tackled, it can lead to starvation.

Additionally, almost 26 million children under 5 years old are suffering from wasting; low weight-for-height which usually happens when a child has not had enough or good quality food, or has had a prolonged illness. Of this 26 million, over 5 million children were at an increased risk of death due to severe wasting.

That this year’s Global Report on Food Crises shows hunger levels in the world still remain alarmingly high is not surprising, but it is a warning for the global community to act urgently to tackle hunger and its root causes – conflict and climate change

Why are world hunger figures rising?

Conflict remains the biggest driver of hunger worldwide, pushing 139 million people in 24 countries into acute food insecurity in 2021, up from around 99 million in 23 countries in in 2020.

Among the other contributors to food insecurity are economic shocks. Global food prices rose to new levels in 2021, which had devastating impacts on the poorest and those already vulnerable and struggling to recover after job and income losses due to Covid-19 restrictions.

Weather extremes were the main causes of food insecurity in eight African countries, and the impact of weather-related disasters on acute food insecurity has intensified since 2020. Weather shocks – in the form of drought, rainfall deficits, flooding and cyclones – have been particularly detrimental in key crises in East, Central and Southern Africa, and Eurasia.

Global hunger in 2022

There is not a lot of optimism for 2022, as food insecurity is expected to increase even further, owing to the conflict in Ukraine and its impact on global food production, energy, food prices and supplies. Many countries included in the report import a large proportion of their wheat, sunflower oil and seeds from Ukraine (and Russia).

Around 193 million people were acutely food insecure last year; this will only get worse with the impacts of the Ukraine conflict on food costs and availability, amidst one of the worst droughts in 40 years in the Horn of Africa.

Global humanitarian and development funding for food crises is failing to match growing needs. It has been steadily falling since 2017, but given the Covid-19 pandemic and the economic fallout from it, particularly for vulnerable communities and households, the current shortfall in funding is disappointing and worrying.

Below we’ll look at four countries with acute food insecurity where Concern work, the issues at play and what our programmes are doing to ease these stresses.

But first it’s helpful to understand some of the terminology used.

- Crisis levels of hunger: some households are not eating enough food and have high levels of malnutrition, while others are adopting irreversible coping mechanisms such as selling assets that support them to make a living, so they can afford to eat a limited amount of food.

- The next level up from that is Emergency: where people are facing extreme food shortages, acute malnutrition and disease levels are excessively high, and the risk of hunger-related death is rapidly increasing.

- And the most severe is Catastrophe: despite using all of their coping strategies, people have almost no food and cannot support their basic needs to survive. Starvation, death and destitution are a tangible reality.

Democratic Republic of Congo

The Democratic Republic of Congo has the largest number of people facing high levels of acute food insecurity. 25.88 million people, approximately 25% of the population, are predicted to be facing crisis levels of hunger or worse.

Conflict and insecurity continue to impact large swathes of the country, restricting the movement of people and goods, and damaging livelihoods. People fleeing violence are left depending on communities that offer them refuge, putting further pressure on these host families. Those who return to their homes lack the confidence and resources to start again, leading to low agricultural production and a dependence on markets to meet household food needs.

Afghanistan

55% of the population of Afghanistan are in crisis level hunger or worse; that’s 22.81 million people. Numbers have risen steadily since 2020, with almost 6 million more people impacted by March 2022.

Urban acute food insecurity has also worsened due to growing unemployment, falling incomes and rising food prices.

While conflict has impacted food security in the past, it’s expected that the level of violence will decrease in 2022. People forced from their homes due to fighting are now returning, but are met with a lack of basic services, little opportunity to earn an income and no family support networks.

Drought is a major contributing factor to food security in Afghanistan, with a second consecutive year of below average winter rains likely to reduce crop production by 20 to 30%.

Sanctions are playing a part in the economy, with limited availability of cash challenging markets, trade and payment of salaries, along with hindering food imports. Unemployment has almost doubled since 2019, to 29%. And the status of foreign aid into the country remains uncertain. All these elements are likely to see the price of the average food basket increase even further.

Concern's Response

Concern is working in 44 extremely poor and vulnerable communities in Northeast Afghanistan, to promote sustainable food production and income earning opportunities. Programme activities have significantly boosted agricultural and livestock productivity, along with improving the collection, storage and management of water resources which allow for sustained agricultural production.

We also work with communities to have plans in place that reduce risks to manmade and natural hazards. Included in this is understanding how climate change and disaster hazards impact livelihoods, and find ways to reduce their impact.

Pakistan

4.69 million people were forecast to be in crisis hunger or worse in May/June 2022 in Pakistan.

High food and fuel prices are impacting the ability of low-income households to buy food, while drought continues to impact wheat production, Pakistan’s main food staple. Winter rainfall is expected to be low in wheat-producing areas of central and northern Pakistan due to current weather patterns, and the harvest season will depend on how much rain falls.

Sudan

Almost 6 million people, 13% of the population, are considered in crisis hunger or worse in Sudan.

Inflation has risen to over 300%, with economic shocks such as Covid-19 and suspension of support from the international community due to a coup in 2021 adding further stress to the economy.

Tight supplies of cereal, above average food prices, reduced household buying power and conflict and displacement are limiting households’ access to food. The amount of wheat planted during the winter season was 28% lower year on year, largely due to shortages of better quality seeds and fertiliser, with the rising price of electricity affecting pump irrigation to water crops.

Main harvest seasons in 2021/2022 were disrupted in two states due to conflict, with violence expected to increase further in 2022. Nationwide protests continue, interrupting people’s access to markets and reducing opportunities for poor urban households to earn a living.

2021 also saw extreme weather events such as heavy rains and flooding, following on from 2020 and the worst floods experienced in the country in almost a century. Climate related events continue to have an impact on people’s ability to produce food and maintain livelihoods.

Concern's Response

Food insecurity has increased in all the areas Concern operates in in Sudan. We reached just under half a million people in 2021, through our development and emergency response programmes.

We’re working with communities to manage acute malnutrition, including providing nutrition information and sensitisation around infant and young child feeding at mother care groups, and providing therapeutic food for the most serious of cases in young children. Kitchen gardens and cooking demonstrations also play a role in providing people with the tools to grow their own food.

Our programmes work with food producers and small farmers, to provide training, run seed fairs, introduce and distribute improved drought tolerant seeds, distribute livestock and share best practices for their care and management.

Resilience to climate change is also an important element of our programming, helping villages and communities create plans in how best to adapt and reduce their risk through strengthening their early warning systems and building community capacity and practices.

* The Global Report on Food Crises is an annual report from the Global Network Against Food Crises (GNAFC), an international alliance of the United Nations, The EU, governmental and non-governmental agencies working together to tackle food crises.