Knowledge Hub

Hunger is a broad concept that often focuses on the physical and psychological sensation of going without food. But in its extreme form, hunger can have a lasting and damaging outcome - increasing mortality rates and decreasing the chances that people have to lead healthy and fulfilling lives.

Extreme hunger is worsening at an unprecedented rate around the world. 828 million people – that's about 10 percent of the global population – regularly go to sleep hungry. And while world hunger rates were on a decline in the past decade, the numbers have started rising again at an alarming rate since 2017.

Today, almost 50 million people are facing emergency levels of hunger across 43 countries. The situation has become so serious in the last couple of years that many countries are now at risk of famine.

Hunger v extreme hunger

The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) describes hunger as the “uncomfortable or painful physical sensation caused by insufficient consumption of dietary energy”. It is a feeling that many of us will have experienced at some point in our lives for a brief time.

However, extreme hunger is when people spend entire days with little or nothing to eat, and is, unfortunately, a common occurrence. It is usually down to food insecurity due to a lack of money and lack of access to food and other resources. When food deprivation happens again and again over a prolonged period of time it threatens normal growth and development and a healthy life.

What are the different levels of extreme hunger?

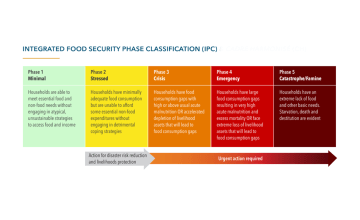

In 2004, the FAO developed the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) system to provide a standardised means to classify the severity and magnitude of food insecurity in different countries or regions. It works on a scale of Phase 1 (no or minimal food insecurity) to Phase 5 (catastrophe or famine). The harmonised tool helps identify where humanitarian assistance to address severe food insecurity is needed most.

Severe and moderate food insecurity

Severe food insecurity is closely associated with extreme hunger. When someone is severely food insecure it means they lack regular access to enough food - and have gone a day or more without eating.

People who are moderately food insecure are also highly vulnerable. Uncertainty about when they will next find food may mean families have to limit their meals to one a day or have to sacrifice other basic needs just to be able to eat.

One in four people around the world - that's 2.3 billion people - experienced moderate or severe food insecurity in 2021.

Famine: the complete exhaustion of food supplies

While many countries across the world face food insecurity, famine is the most serious IPC phase and is only declared when certain conditions are met.

Its main criteria is – that within a specific region - at least 20% of households face an extreme lack of food, at least 30% of children are acutely malnourished, and two people in every 10,000 are dying each day.

Famine is the end of the road and the complete exhaustion of food supplies in most households in a specific region.

What are the symptoms of extreme hunger?

Prolonged periods of extreme hunger can lead to malnutrition, which occurs when the body lacks sufficient vitamins, minerals and other nutrients needed to thrive. Generally, there are two ways that malnutrition is diagnosed – chronic and acute.

Chronic malnutrition, or stunting

Chronic malnutrition or stunting is when a child is too short for their age. This happens when children do not have access to a diverse range of nutritious food. Stunted growth in children can cause lifelong physical and cognitive damage, while chronic malnutrition can leave children more susceptible to infections.

Acute malnutrition, or wasting

Acute malnutrition or wasting is when a person is too thin for their height. This can happen suddenly, caused by a severe hunger crisis, or something that occurs gradually but persistently. Acute malnutrition can be treated, but if it isn't, an acutely malnourished child can be nine times more likely to die than a well-nourished child.

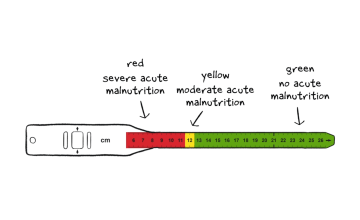

The two forms of acute malnutrition are moderate and severe, both of which can be diagnosed using a mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) tape.

- Moderate acute malnutrition (MAM)

Also known as moderate wasting, moderate acute malnutrition is when a child's MUAC reading is between 115mm and 125mm, or when their weight is very low compared to other children of the same height. Children who are moderately acutely malnourished require supplementary feeding.

- Severe acute malnutrition (SAM)

Severe acute malnutrition (SAM) is more serious than moderate acute malnutrition. When a child has a MUAC reading below 115mm or their weight is extremely low compared to other children of the same height they require immediate therapeutic nutritional care and basic medical treatment.

What are the causes of extreme hunger?

A complex mix of issues, such as poverty, gender inequality, conflict, soaring prices and climate change all play a role in keeping food out of reach for millions of families around the world.

Poverty

Poverty is the main cause of extreme hunger. Globally, 719 million people live in extreme poverty, surviving on less than $2.15 a day. Without sufficient and sustainable livelihoods, families cannot afford access to nutritious food. The result is that one in three children in low- and middle-income countries live with chronic undernutrition.

The cycle of poverty and hunger can be difficult to break out of. People who experience extreme hunger are affected by low levels of energy and reduced mental capacity, which in turn makes it difficult for them to work or learn.

Climate change

Increasingly, extreme climate variations are becoming a key force behind extreme hunger worldwide. The number of climate-related disasters, such as drought, floods and severe heat, has doubled since the early 1990s.

Rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns have dramatic impacts on crops and livestock, which in turn have devastating implications for food security and hunger.

Conflict and instability

Hunger is both a cause and consequence of conflict. More than 85% of people experiencing hunger crises live in conflict-affected countries, many of which are caused by disputes over food and water, or the resources needed to produce them. Conflict disrupts harvests, impedes the delivery of humanitarian assistance and forces families to become displaced.

In some places, hunger is weaponised by armed groups, who deliberately destroy crops and livestock and deny communities access to food. Children living in regions experiencing conflict are more likely to die as a result of hunger and disease, than fighting.

Gender inequality

Women and girls are disproportionately affected by hunger – representing 60% of people negatively impacted by food insecurity. In many places, women are more likely to skip meals, eat the least and eat last, despite being responsible for sourcing and preparing food for their families. 150 million more women experienced extreme hungry in 2021 compared to men.

Covid, Ukraine conflict and soaring prices

Economic shocks brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic, plus the combination of soaring global food prices, the impact of the conflict in Ukraine, widespread supply chain disruptions, job losses and an uneven global economic recovery, have all contributed to the rise of global hunger.

What is Concern doing to combat extreme hunger?

Building resilience to climate change

Almost all of the communities that Concern works alongside are engaged in farming and food production. Many of them are also on the frontline of climate change and regularly face food shortages.

We work with rural communities to anticipate, respond to and build resilience against the shocks and stresses of climate extremes.

In places like Malawi, we promote Climate Smart Agriculture - an approach that helps families to better use and manage the natural resources available to them. We also work with them to find more efficient methods to harvest food for their families and to sell at market.

Emergency response

Droughts, floods, food crises and other emergencies turn lives upside down and can leave people facing extreme hunger.

Concern provides emergency food for communities experiencing high levels of food insecurity. In Kenya, for example, we have distributed vital food baskets to people impacted by severe drought and loss of livestock.

We also support local health workers to provide treatment services for children who suffer from severe and moderate acute malnutrition. For SAM children, this includes basic medical treatment and a weekly ration of ready-to-use-therapeutic food that they can eat daily at home until they regain their weight. For MAM children, it is usually a nutritious ration to supplement the food they get at home.

Boosting social protection

Social welfare systems are an effective means to assist people in times of crises. But for many of the world’s most vulnerable communities faced with severe food insecurity, there is no such social safety net.

Concern aims to provide this assistance through cash transfers, enabling people to buy the essentials needed to survive, which, in almost all cases, is primarily food.

Reduce the risk of disasters

As well as responding to immediate emergencies, Concern also works to mitigate potential losses in the wake of disasters for those who stand to lose the most. This approach is called Disaster Risk Reduction.

For many of the communities with whom we work, the prospect of losing their harvest is the very definition of disaster. Simple techniques to protect and diversify crops, along with protecting livestock, can be effective in combatting food insecurity and extreme hunger.

Fostering gender equality

Gender equality is another key solution to extreme hunger – especially when it comes to farming and maternal and child health.

By prioritising women’s health and nutrition, we can prevent not only health complications for them but also for their children.

Our livelihoods programmes also give women equal access to the same resources that men have – these include credit and loans schemes, access to land, water, seeds, tools and training. This ensures that women farmers are able to grow food for their family, and is especially important when a hunger crisis strikes.

Other ways to help

Donate now

Give a one-off, or a monthly, donation today.

Join an event

From mountain trekking to marathon running, join us for one of our many exciting outdoor events!

Buy a gift

With an extensive range of alternative gifts, we have something to suit everybody.

Leave a gift in your will

Leave the world a better place with a life-changing legacy.

Become a corporate supporter

We partner with a range of organisations that share our passion and the results have been fantastic.

Create your own fundraising event

Raise money for Concern by organising your own charity fundraising event.