Knowledge Hub

Gender inequality is the most common form of inequality across the globe. It is also one of the biggest barriers to ending extreme poverty. Here we look at why women are more likely to be poor and how important it is to place them at the forefront of humanitarian and development interventions.

‘Feminisation of poverty’ is a term that was coined in the 1970s by researcher Diana Pearce, who worked on gender and poverty in the United States. The term gained global status at the Fourth United Nations Conference on Women in 1995 and is now used extensively in the debate on international development and humanitarian aid. It refers to the phenomenon that women and children are disproportionately represented among the world’s poor and are more likely than men to live below the poverty line. The concept is relatively simple, but the reasons for it are complex and many.

Table of contents

Why are women more likely to be poor?

Persistent inequalities in all societies mean women and girls are disproportionately affected by poverty and oppression. There are many complex and interconnected issues that perpetuate poverty and are a barrier to gender equality, just some of these are;

- Unequal economic opportunities, including access to livelihoods and the gender pay gap

- Limited access to quality education

- Health and nutrition challenges

- Lack of government representation

- Gender-based violence

- Conflict

However, there are also less tangible causes of inequality– and are a result of everyday gender biases present in societies and governments. Such biases span a multitude of areas, themes and levels of severity; but all result in women and girls being disproportionately affected by poverty and oppression across the world.

To put this into context, a UN report, from 2023, found that almost 90% of men and women hold some sort of bias against females. The "Gender Social Norms" index analysed biases in areas such as politics and education in 80 countries, covering 85% of the world’s population. Here are a few of the findings:

- Globally, close to 50% of men said they had more right to a job than women;

- Nearly half of the world’s men and women feel that men make better political leaders;

- More than a quarter of respondents thought it was acceptable for men to hit their partners.

The study also concluded that the world is not on track to achieve gender equality by 2030.

How does this manifest itself in the world’s poorest places?

The impact of gender inequality is more pronounced in the world’s poorest countries, where many women and girls still do not have access to or control over even the most basic resources and services. They live in fear of gender-based violence (GBV), are denied education and have no say over decisions in their homes. This becomes unmistakably apparent when girls start missing out on opportunities at a young age.

Families living in poverty often decide to prioritise education, sending their sons to school instead of their daughters. Moreover, if girls do not have adequate information about their periods or access to menstrual products, safe water and hygiene facilities, they may also have to miss school. Less education means less likelihood of employment, which is further exacerbated by household chores systematically falling on the women and girls, creating longer working hours and even fewer opportunities to earn an income.

How can we bring about change?

Strengthening gender equality is one of the most fundamental accelerators of sustainable development. Empowering women is a key driver for ending hunger, poverty and conflict and for building peace and prosperity. Positioning gender at the forefront of programme interventions and understanding the gender continuum challenges inequalities and when applied, creates positive change for women and girls.

The gender continuum

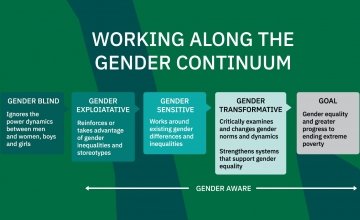

Introduced by the Interagency Gender Working Group, the Gender Continuum is a framework that is used to ensure gender equity is successfully integrated into humanitarian and development aid policies and programmes. It helps organisations understand the concept of gender relations (or roles and norms) and how they can impact the results of their work.

There are three approaches that integrate gender into interventions; gender exploitative, gender sensitive and gender transformative, which are described in the graphic below.

A gender exploitative approach takes advantage of gender inequalities and stereotypes in pursuit of narrowly focused project outcomes. This is likely to achieve only short-term results and may well exacerbate gender inequality in the long run. Since one of the fundamental principles of development is to “do no harm” then only two approaches remain, gender sensitive and gender transformative.

Moving from gender sensitive to gender transformative

Gender Sensitive

A gender sensitive approach to development and humanitarian aid – means identifying and taking into account the different needs, abilities, and opportunities of girls, boys, women and men. However, while it recognises gender differences and accommodates them in pursuit of achieving our goal of ending extreme poverty, it does not necessarily address root causes or challenge harmful stereotypes or norms.

Instead, in order to achieve its goals, it works around, adjusts to, or compensates for gender differences, norms, and inequities – still giving the programme approach value. For example, a programme that aims to provide services or training to women in a context where women are not allowed out of the immediate area (community or village) without the husband’s permission, instead brings services or training to the women. This does not directly address the social gender norms and power dynamics that are affecting women’s participation in the programme activity, but instead, it finds a way around these obstacles to achieve its objective.

Gender transformative

The ultimate aim, however, is to move from 'gender sensitive' to 'gender transformative' in all development and humanitarian work. This means working with communities to transform the root causes of gender inequality and tackle power imbalances at different levels of society.

Gender-transformative programmes build in opportunities that challenge existing harmful gender norms and stereotypes to:

- Improve equitable decision making;

- Increase access to resources;

- Improve the distribution of workload fairly between men and women;

- Reduce GBV and engage women and men in dialogue that will create greater equality and,

- Ultimately lead to more sustainable solutions that benefit all.

For example, implementing programmes that work directly with women on practical needs, such as vocational skills, income generation and budget management, as well as soft skills such as self-esteem or public speaking. At the same time, they work with women, men and traditional or religious leaders to reflect on gender norms that are supportive of joint decision making, of women taking on productive roles and improved communications through couples’ dialogue.

Why is this relevant now?

Despite some progress, Sustainable Development Goal 5, ‘Achieve full gender equality and empowering all women and girls’ remains unreached. The World Economic Forum (WEF) estimates that at the current rate of progress, global gender equality will not be achieved for another 131 years.

Girls are three times more likely than boys to miss out on an education. Globally, 75% of unpaid work is performed by women and one in three women worldwide have experienced some form of gender-based violence.

Concern believes that women and girls are the primary agents of change in the community and for the last 50 years have placed women’s empowerment at the heart of our humanitarian and development programmes. Every programme Concern implements are gender sensitive and our ultimate aim is to move to gender-transformative in all our humanitarian and development interventions. This means working with communities to develop programmes that transform the root causes of gender inequality at multiple layers of society – from the individual to the institutional and national.

We believe we can all be women of change, and by changing one woman’s life we change many more.

Sign up to our newsletter and other emails to join the fight to end extreme poverty

Other ways to help

Donate now

Give a one-off, or a monthly, donation today.

Join an event

From mountain trekking to marathon running, join us for one of our many exciting outdoor events!

Buy a gift

With an extensive range of alternative gifts, we have something to suit everybody.

Leave a gift in your will

Leave the world a better place with a life-changing legacy.

Become a corporate supporter

We partner with a range of organisations that share our passion and the results have been fantastic.

Create your own fundraising event

Raise money for Concern by organising your own charity fundraising event.