Knowledge Hub

One mum's journey to discover if her child has a killer disease.

22-year-old single mum Aline Nsabimana is concerned for the health of her three-month-old son Roger after he woke with a fever and began coughing two nights ago. She fears he may have pneumonia - a killer illness.

Globally, two children die from pneumonia every minute. It is the single biggest cause of child deaths through infectious disease - claiming 880,000 lives worldwide in 2016.

Aline hopes against the worse, despite Roger showing no signs of improvement and knowing that he hasn't been vaccinated.

It all began two days ago during the night.

Not the first time he's been ill

This morning at five o’clock, Aline sets off from her home in Burara in a remote part of northern Burundi to walk barefoot for an hour to the nearest health centre, cradling little Roger close to her.

This isn’t the first time her only child has been ill – he’s just three months old and has already had several bouts of malaria – the most recent, diagnosed yesterday by a Community Health Worker.

Now Aline is concerned that will be compounded by pneumonia.

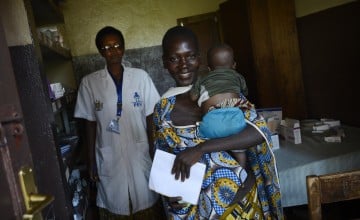

At the rural clinic in Burara, Kirundo, nurse Oréne Nahimana examines Roger. She monitors his body temperature and the rate of his breathing - all indicators to determine if he has pneumonia.

These are tense moments for mum Aline.

The tragedy for many families in a similar situation is that pneumonia is preventable through vaccination. In 2015, many of the world’s governments made a pledge under the Sustainable Development Goals to work for a world in which no child would suffer a preventable death by 2030.

But pneumonia deaths are falling more slowly than other major causes of child mortality. That is mainly because it is a disease of poverty. Fatalities are concentrated in the world’s poorest countries, and it is the poorest and most vulnerable like baby Roger, who face the greatest risks.

Within a few minutes, Nurse Nahimana confirms the news that Roger has pneumonia.

She prescribes a course of antibiotics to be administered at home. Aline will also be expected to bring Roger back to the clinic in a few days' time to check on his progress.

10 cases of pneumonia a month in one rural community

Nurse Nahimana, who is also the deputy head of the clinic in Burara which serves around 30,000 people, says they treat an average of 10 cases of pneumonia a month, with much higher rates of children with coughs and flu.

There are times during the year when those numbers increase and there are a lot of cases. Pneumonia, diarrhoea and malaria are the main causes of child deaths and yet they can be easily prevented.

Saving children from pneumonia requires urgent action and recognising the danger signs. Often children are brought in too late when they are already very sick or seriously ill. It is a major problem, not just in this province - Kirundo, but across Burundi where an estimated 16,000 children die each year from pneumonia.

In this instance, however, Roger has been diagnosed in time thanks in part to the quick actions of the local Concern-supported Community Health Worker.

Concern Worldwide has trained almost 550 Community Health Workers in Burundi to spot the early signs of fatal illnesses like pneumonia. They have also been instructed in treating coughs, malaria and diarrhoea on the spot and refer more serious cases to skilled healthcare staff at the local clinic. The approach of the CHWs is especially effective because it focuses on stopping easily preventable diseases at community level, before they take hold.

“In this case, a Community Health Worker (CHW) carried out a malaria test on the child and it was positive," says Nurse Nahimana.

"They prescribed medication and the child has already started a three–day course of treatment. But because of the seriousness of the cough, the CHW referred the child to the clinic.

“Community Health Workers help us very much. They have been taught to identify and treat certain illnesses there and then. If it is more serious, they refer them to us."

'If I hadn't acted when I did, my son would be very sick'

Relieved, Aline leaves the clinic with the amoxicillin medication she needs to treat Roger.

Now, I am hopeful.

Once back home, Aline gives Roger his first dose of medicine with the help of a neighbour. Within minutes, he settles and falls asleep in his mother's arms.

Outside her house which she shares with her 75-year-old grandmother Margueritte and cousin Honorine (16), Aline joins her family and neighbours to shell and sort the dried beans they have just harvested.

Her aunt offers to nurse sleeping Roger, while Aline takes time to process all that she's been through. The stress of the past few days has taken its toll.

Aline and her family earn money from casual work and often struggle to meet their daily needs. Sometimes, they are loaned a plot of land to grow beans, corn and sorghum – sharing half the harvest with the owner. Most of the other half they keep for themselves, retaining a little to sell at market for some income. But often, it is not enough. A kilo of multi-coloured beans sells for £0.30 (700BIF), while yellow beans fetch double.

"If we don’t find casual labour, then we have no money to buy food. At the moment, we are harvesting beans. But we won’t have any cassava or sweet potatoes this season because of the sun and lack of rain," says Aline.

When we have food, we eat twice a day. But, often we only have one meal a day. It happens a lot that we only eat once.

That lack of access to enough nutritious food that Aline and her family are experiencing is a big factor in childhood mortality from pneumonia, particularly when it leads to malnutrition - which accounts for about half of all deaths. Children who are undernourished face an increased risk of pneumonia, as their body's effectiveness to overcome the demands of the illness is reduced.

As Roger awakes, Aline is content for the first time in days. Her sick son is starting to make a recovery.

Since arriving back from the clinic, Roger is beginning to feed again. My heart has gone back into its proper place again! I’m much calmer because I know that he’s been treated.

The quick intervention of a local health worker and nurse have helped save Roger's life. For now, he is out of danger. But the threat still exists for countless vulnerable children like him living in rural communities around the world in conditions of extreme poverty and inequality. Without prevention, fast diagnosis and treatment, many of them may not be as lucky.